Have you ever wondered why all beers have that strong, characteristic smell? Or why you could tell the smell of cannabis apart from any other plant? The answer is simple – terpenes.

These 55,000 different molecules are responsible for a majority of the odors and fragrances around us, from a pine forest, to the air diffuser in your house 1–3. They all share the same precursor, isoprene, and because of that, they are all related and have similar molecular structures. Unfortunately, it is this uncanny similarity that makes their analysis so challenging; we still lack a complete list of which terpenes expected to be found in each given plant species 1,2.

Many different methods have been developed in an effort to provide a time-optimized and straightforward analysis. Gas chromatography (GC) is usually center stage due to the volatility of the terpenes. Therefore, there is significant concern with the type of GC detector used 2.

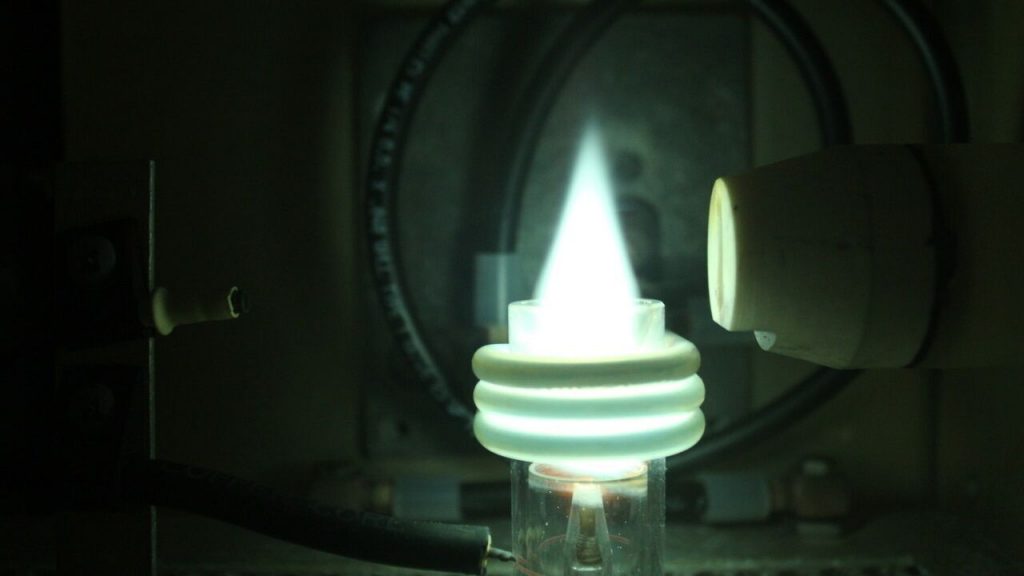

The flame ionization detector (FID) is a good quantitative detector for GC, but qualitatively it does not provide any information, except for retention time; the differentiation between terpene species is achieved solely by use of retention indices (RI), which are based on elution times from a particular GC stationary phase. The best part of the FID is its low cost, reliability, and relatively easy interface, which make it an effective tool for quality control (QC) but less so with respect to research and discovery 2.

The primary choice for a research setting is the mass spectrometer (MS) detector. It is more expensive and complicated than FID, but importantly, it provides both good quantitative capabilities, and it provides mass spectra for each species that elutes from the chromatograph. However, for terpene analysis, it may still not be the best detector choice. Since terpene class molecules share many structural and functional similarities, even their fragmentation and sub-sequential identification by MS may lead to inconsistent results, which need to be confirmed by use of RI. Still, MS is a better qualitative analysis tool than the FID, especially for distinguishing non-isobaric terpenes 2.

Recently, new technology based on vacuum ultraviolet spectroscopy (VUV) has been developed as a new GC detector. The VUV detector enables analysis of virtually all molecules; virtually all chemical compounds absorb light in the range in the 125-240 nm wavelength range probed by the detector, making it an essentially universal detector 4–11. Previously, spectroscopic absorption detectors for GC have lacked sufficient energy to measure absorption of most GC-amenable species. The VUV detector fills a niche, which is complementary to MS detection in terms of the qualitative information it provides.

With the VUV detector, each compound exhibits its own unique absorbance spectrum. Even isomers and isobars, which are prevalent in terpene mixtures and can be difficult to distinguish different species by their electron ionization mass spectra, can be well differentiated based on their VUV spectra 6,9,10. Nevertheless, because analytes exhibit different spectra, it is not required to achieve a perfect chromatographic separation of the mixture components. Co-eluting peaks can be separated post-run through the use of library spectra and software inherent to the instrument 4,10. This ability is called “deconvolution”, and it is based on the fact that two co-eluting terpenes will give a peak with an absorbance spectrum equal to the sum of the two single absorbance spectra 4. Figure 1 shows the deconvolution process for two co-eluting terpenes, camphor and (-)-isopulegol. Due to their different absorbance spectra (Figure 1C), it is possible to fully separate the two peaks in post-run, obtaining sharp peaks for both analytes 6.

The deconvolution process has been shown to yield precise and accurate results. Thus, chromatographic resolution can be sacrificed in favor of spectroscopic resolution; this enables the development of methods with faster run times. With the ability to deconvolve unresolved peaks, a long temperature ramp to chromatographically separate all isomeric terpenes is not required 6. Additionally, the presence of coeluting components, which might normally go undetected with some GC detectors, can be easily judged based on comparison of the measured spectra with pure reference spectra contained in the VUV spectral library.

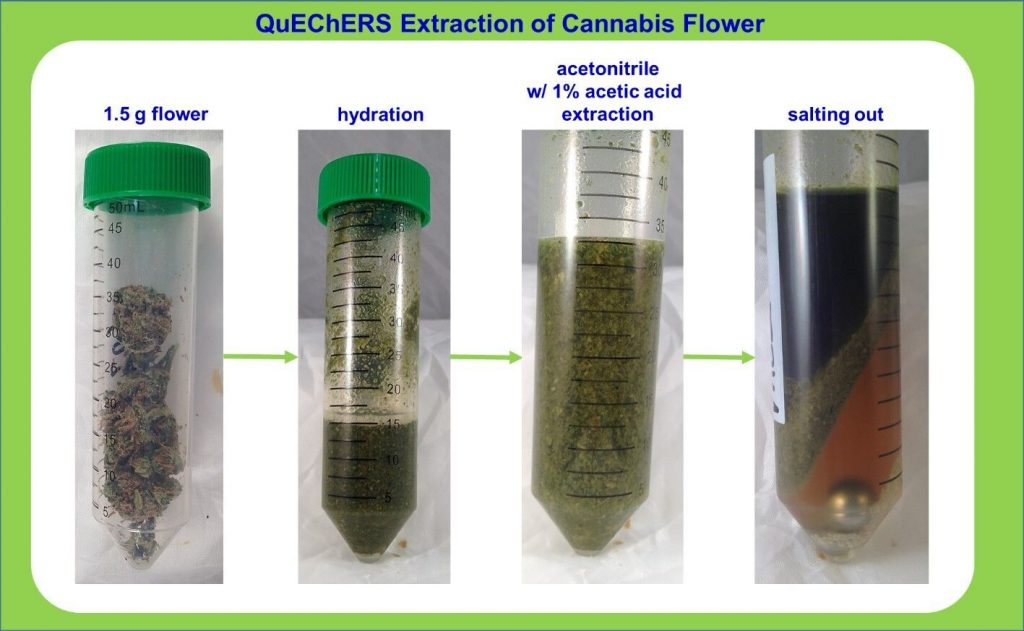

The other issue in terpenes analysis is the extraction process. Terpenes can be extracted with the use of solvents (e.g., methanol, ethanol, hexane, and cyclohexane, among others), but the process is usually time-consuming, costly and not so environmentally-friendly 2. The plant needs to be manually crushed and then aliquots of solvent are used to extract components from the plant, ideally at least 3 times and combined to achieve acceptable results. The problem is that some terpenes may respond better to a certain solvent, making their extraction easier and more optimized than for others 2. The choice of solvent can cause discrimination against the extraction some terpenes, which limits the comprehensiveness of analysis.

Headspace is another technique that can be used for the sample preparation of terpenes. Headspace sampling is based on heating the solid or liquid sample inside a sealed vial, and then analyzing the air above it after sufficient equilibration. In this way, only volatile analytes are extracted from the solid/liquid sample into the gas phase; this allows relatively interference-free sampling 12–14.

How do we know whether our extraction analysis methods are correct and comprehensive for a certain plant sample? Unfortunately, there is not a complete list of available molecules for each plant species, and even if two specimens may smell really similar to our nose, their terpenes profiles may be notably different. When working with a new plant material, it is difficult to predict the extraction efficiency for the vast array of terpenes that may be present. We can only perform it with different extraction and detection methods, and compare the results.

The route for a comprehensive and fast analysis of terpenes is therefore still long; however, their intoxicating aromas and inherent medicinal value has provided a growing impetus for researchers around the world. Considering the evolving importance of Cannabis and the growing body of evidence on the synergistic effects between terpenes and cannabinoids, it is likely that newly improved extraction and analysis methods will be developed, paving the way for a more complete list of terpene species that can be found in different cultivars. The use of new analytical technologies, such as the VUV detector for GC, should aid considerably in this endeavor.

References:

[1] Breitmaier E., Terpenes: Flavors, Fragrances, Pharmaca, Pheromones. John Wiley & Sons 2006.

[2] Leghissa A., Hildenbrand Z. L., Schug K. A., A Review of Methods for the Chemical Characterization of Cannabis Natural Products. J. Sep. Sci.2018, 41, 398–415 .

[3] Benvenuto E., Misra B. B., Stehle F., Andre C. M., Hausman J.-F., Guerriero G., Cannabis sativa: The Plant of the Thousand and One Molecules. Front. Plant Sci2016, 719, DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00019.

[4] Schug K. A., Sawicki I., Carlton D. D., Fan H.,Mcnair H. M.,Nimmo J. P., Kroll P.,Smuts J.,Walsh P., Harrison D., Vacuum Ultraviolet Detector for Gas Chromatography. Anal. Chem.2014, 86, 8329–8335 .

[5] Fan H.,Smuts J., Walsh P.,Harrison D., Schug K. A., Gas chromatography-vacuum ultraviolet spectroscopy for multiclass pesticide identification. J. Chromatogr. A2015, DOI: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.02.035.

[6] Qiu C.,Smuts J., Schug K. A., Analysis of terpenes and turpentines using gas chromatography with vacuum ultraviolet detection. J. Sep. Sci.2017, 40, 869–877 .

[7] Leghissa A., Smuts J., Qiu C., Hildenbrand Z. L., Schug K. A., Detection of cannabinoids and cannabinoid metabolites using gas chromatography-vacuum ultraviolet spectroscopy. Sep. Sci. Plus2018, 1.

[8] Bai L.,Smuts J., Walsh P., Fan H., Hildenbrand Z., Wong D., Wetz D., Schug K. A., Permanent gas analysis using gas chromatography with vacuum ultraviolet detection. J. Chromatogr. A2015,1388, 244–250 .

[9] Skultety L., Frycak P., Qiu C.,Smuts J., Shear-Laude L., Lemr K., Mao J. X., Kroll P., Schug K. A., Szewczak A., Vaught C., Lurie I., Havlicek V., Resolution of isomeric new designer stimulants using gas chromatography – Vacuum ultraviolet spectroscopy and theoretical computations. Anal. Chim. Acta2017, 971, 55–67 .

[10] Bai L., Smuts J., Walsh P., Qiu C., McNair H. M., Schug K. ., Pseudo-absolute quantitative analysis using gas chromatography–vacuum ultraviolet spectroscopy–a tutorial. Anal. Chim. Acta2017, 953, 10–22 .

[11] Schenk J., Nagy G., Pohl N. L. B., Leghissa A., Smuts J., Schug K. A., Identification and deconvolution of carbohydrates with gas chromatography-vacuum ultraviolet spectroscopy. J. Chromatogr. A2017, 1513, 210–221 .

[12] Van Opstaele F., De Causmaecker B., Aerts G., De Cooman L., Characterization of novel varietal floral hop aromas by headspace solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry/olfactometry. J. Agric. Food Chem.2012, 60, 12270−12281 .

[13] Hamm S., Bleton J., Connan J., Tchapla A., A chemical investigation by headspace SPME and GC-MS of volatile and semi-volatile terpenes in various olibanum samples. Phytochemistry2005,66, 1499–1514 .

[14] Aberl A., Coelhan M., Determination of volatile compounds in different hop Varieties by headspace-trap GC/MS-in comparison with conventional hop essential oil analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem.2012, 60, 2785−2792 .