Polyploidy in Cannabis

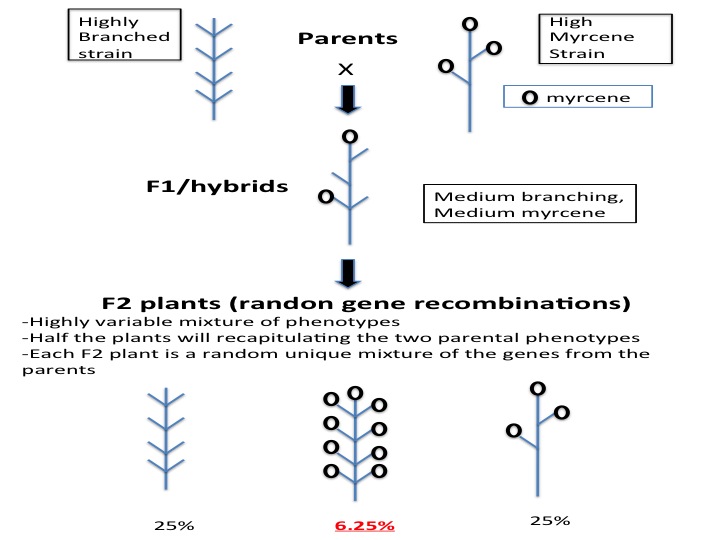

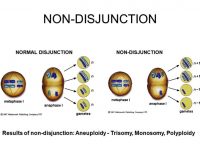

Polyploidy is defined as containing more than two homologous sets of chromosomes. Most species are diploid (all animals) and chromosomal duplications are usually lethal, even partial duplications have devastating effects (Down’s syndrome). Plants are unique as in being able to somewhat “tolerate” chromosomal duplications. We often observe hybrid vigor in the F1, while the progeny of the F1 (F2) will produce mostly sickly or dead plants, as the chromosomes are unable to cleanly segregate.

Chromosomal duplications, either one chromosome or the whole genome, happen frequently in nature, and actually serves as a mechanism for evolution. However the vast majority (>99.99%) results in lethality.

Thus there is polyploidy in Cannabis, and a few examples are supported by scientific evidence. The initial hybrid may show superior phenotypes and can be propagated through cloning, but there may be little potential for successful breeding with these plants.

Epigenetics and Phenotypic Consistency in Clones

One mechanism of turning off genes is by the DNA becoming physically inaccessible due to a structure resembling a ball. In addition, making molecules similar to DNA (RNA) that prevents expression of a gene can turn off certain genes. Both mechanisms are generally termed epigenetics.

Epigenetic regulation is often dependent on concentrations of certain proteins. Through the repeated process of cloning, it is possible that some of these proteins may be diluted, due to so many total cell divisions and epigenetic control of gene expression can be attenuated and results in phenotypic variability.

Sexual reproduction, and possibly tissue culture propagation, may re-establish complete epigenetic gene regulation, however the science is lacking. Epigenetic gene regulation is one of the hottest scientific topics and is being heavily investigated in many species including humans.

Hermaphrodites and Sex Determination

Cannabis is an extremely interesting genus (species?) for researching sex determination. Plants are usually either monoecious (both male and female organs on a single plant), or dioecious, separate sexes. Sex determination has evolved many times in many species. Comparing the mechanisms of sex determination in different organisms provides valuable opportunities to contrast and compare, thereby developing techniques to control sex determinations.

Cannabis is considered a male if it contains a Y-chromosome. Females have two X chromosomes. Even though female Cannabis plants do not have the “male” chromosome, they are capable of producing viable pollen (hermaphrodite) that is the source of feminized seeds. Therefore, the genes required to make pollen are NOT on the Y-chromosome, but are located throughout the remainder of the Cannabis genome. However, DNA based tests are available to identify Male Associated Sequence (MAS) that can be used as a test for the Y-chromosome in seedlings/plants.

Natural hermaphrodites may have resulted from Polyploidization (XXXY), or spontaneous hermaphrodites could be a result of epigenetic effects, which may be sensitive to the environment and specific chemical treatments.

Feminized seeds will still have genes segregating, thus they are not genetically identical. This shouldn’t lead to a necessary decrease in health, but could. A clone does not have this problem.

The other issue is that “inbreeding depression” is a common biological phenomenon, where if you are too inbred, it is bad…like humans. Feminized seeds are truly inbred. Each generation will decrease Heterozygosity, but some seeds (lines) may be unhealthy and thus are not ideal plants for a grower.

GMO– The Future of Cannabis?

Is there GMO (genetically modified organism) Cannabis? Probably, but it is likely in a lab somewhere…deep underground! Companies will make GMO Cannabis. One huge advantage to doing so is that you create patentable material…it is unique and it has been created.

The definition of a GMO is…well, undefined. New techniques exist whereby a single nucleotide can be changed out of 820 million and no “foreign” DNA remains in the plant. If this nucleotide change already exists in the Cannabis gene pool, it could happen naturally and may not be considered a GMO. This debate will continue for years or decades.

Proponents of GMO plants cite the substantial increase in productivity and yield, which is supported by science. What remains to be determined, and is being studied, are the long-term effects on the environment, ecosystem and individual species, in both plants and animals. Science-based opponent arguments follow the logic that each species has evolved within itself a homeostasis and messing with its genes can cause drastic changes in how this GMO acts in the environment/ecosystem (Frankenstein effect). Similarly, introducing an altered organism into a balanced ecosystem can lead to drastic changes in the dynamics of the species occupying those ecological niches. As in most things in life, it is not black and white; what is required is a solid understanding of the risks of each GMO, and for science to prove or disprove the benefits and risks of GMO crops.